In November of 1942, Congress lowered the minimum draft age to 18. Anticipating fierce Axis resistance in North Africa, Europe and the Pacific, military command quickly took advantage of the opportunity: By the war’s end, over 11 million men had been selected to fight.

The draft took an immense toll on universities across the country. As the war dragged on, fewer and fewer men were afforded the opportunity to enroll in post-secondary institutions. Many universities came close to shutting down, and some did.

While deferment was uncommon, the law provided that, in some instances, men seeking an education in math, physics, engineering, medicine or other science-oriented fields could postpone their service until after graduation. Those seeking an education in politics, law, history, the classics or any other field were not so lucky; these subjects were simply not considered important enough for the war effort.

The war ended in 1945, but immediately another conflict began: the Cold War. Aiming to outdo the United Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in virtually all facets of life—athletically, culturally, but above all else, scientifically and militarily—the US government began to emphasize education in math and the sciences to a degree never before seen in formal education.

Combined with the newly-passed GI Bill—an act that allowed servicemen to receive a tuition-free college education after the war—this emphasis meant that there were more teachers than ever qualified to teach science and math in K-12 schools across the country.

This emphasis has never quite waned, and today’s students still feel much of its effects. Many people my age can speak of their experience with Hour of Code, a computer programming event held in K-12 schools across the country, and the incessant reminders of the importance of math, the sciences and computer programming from a young age. An effect of this is also seen in Fishers High School’s own course requirements: Students are required to enroll in a math or quantitative reasoning class each year, even if all graduation requirements in math are met. Today, coursework in the sciences, technology, engineering and math (STEM) is put on a pedestal above all else.

But this was not always the case. In fact, education in subjects now deemed relatively unimportant and “unemployable” was the norm for thousands of years.

Until only recently, higher education in the West was largely rooted in ideas developed in ancient Athens and Rome. There, the idea of the trivium and quadrivium were developed. Together, these were believed to cultivate the qualities of a good citizen, and represented a broad education in several fields—language, persuasion and critical thinking, with other fields later added, like mathematics, the arts and the study of the cosmos.

Over time, the trivium and quadrivium developed into what is today considered the “liberal arts”—a term used to describe a holistic education that includes coursework in the natural sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities.

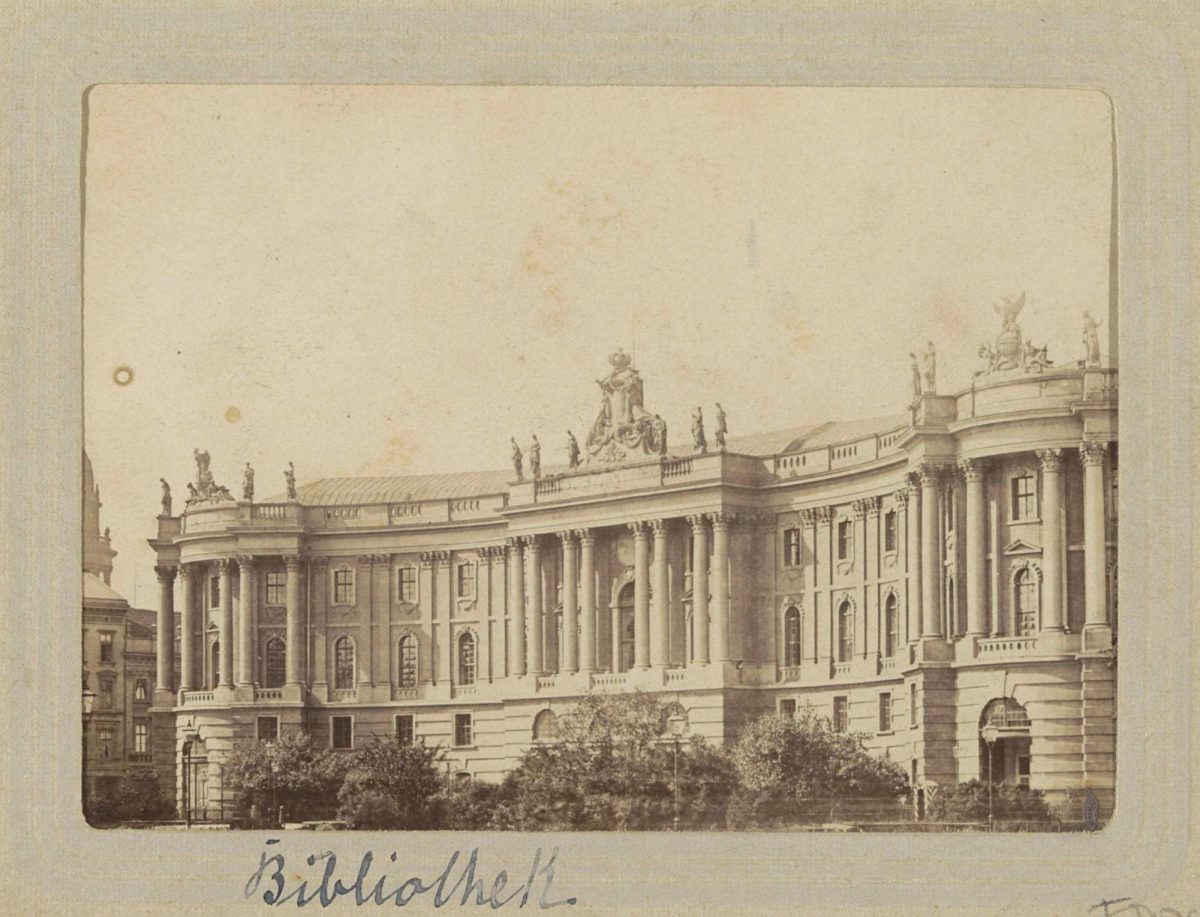

Wilhelm von Humboldt, a German philosopher, linguist and diplomat, was such a staunch proponent of what came to be known as the “liberal arts” that, in 1810, he founded the Humboldt University of Berlin based on what he believed to be “the perfect education.”

In a letter to the Prussian King Frederick William III, Humboldt outlined what he believed to be of utmost importance in education.

There are undeniably certain kinds of knowledge that must be of a general nature and, more importantly, a certain cultivation of the mind and character that nobody can afford to be without. People obviously cannot be good craftworkers, merchants, soldiers or businessmen unless, regardless of their occupation, they are good, upstanding and— according to their condition—well-informed human beings and citizens. If this basis is laid through schooling, vocational skills are easily acquired later on, and a person is always free to move from one occupation to another, as so often happens in life.

Today’s education, unlike Humboldt’s model, lays its ultimate purpose in providing people with a job. This is largely why STEM has been stressed as much as it has, and why the arts and humanities have been cast aside. While this is important—education should provide students the skills to thrive in the workforce—it should not act as pure vocational training.

More than ever, today’s education must foster empathy and a love for learning, and this is done no better than through a holistic, liberal arts approach.

For most of its existence, higher education in the US did, in fact, follow the centuries-old holistic model. Many universities required that students take courses in Latin, Western literature, mathematics and the natural and social sciences, among other things. It wasn’t until the postwar period that these requirements were significantly stripped back, forming the limited “general education requirements” that students across the country dread today. Only a select few universities, like the University of Chicago, still maintain their strict core curriculum.

At around the same time, there began a “careerist focus” within higher education. Professional schools quickly grew in size and funding, and their number of required undergraduate prerequisites grew to such large amounts that students had fewer and fewer slots to take anything but hyper-specific, career-oriented classes. Unlike before, students were no longer encouraged to take classes outside their major. Before long a “careerist sentiment” existed not only in the minds of university administrators, but also students.

In my experience, I have even found this careerism seep itself into high school. Since my freshman year, I have heard many of my peers bemoan several of their required courses, most often those in the humanities, arts or social sciences. I often hear them complain that these courses “are not relevant” to the career they want to pursue. (And I, perhaps a bit hypocritically, have contributed to this as well; for me, the frustration was with math!)

Additionally, it has become hard to avoid careerist framing when considering what classes to take. In the FHS Course Guide, many upper-level classes are described with career or education specialization in mind. STEM classes, like AP Computer Science Principles and International Baccalaureate Mathematics: Analysis and Approaches, are described as “helpful in careers” and “intended for students who wish to pursue studies in mathematics at university or subjects that have a large mathematical content.” Even art classes, like Drawing IV, are described as “designed… for students planning to major in art.”

The issue with this kind of framing is that it encourages a careerist mindset at such a young age and discourages students from taking classes they might otherwise find interest in. Considering your interests and future is one thing; shutting out (possibly life-changing) learning opportunities for the ultimate goal of “career advancement” at the age of 16 is another. No student should refrain nor be discouraged from taking an upper-level drawing class, for example, just because they do not plan to major in art.

Of course, it would be silly to deny that education at the secondary and post-secondary levels does not nor should not provide you with the means to enter the workforce. Often, education is a means of social and economic mobility, and the things taught to you in high school and college should provide you with the means to provide for yourself.

But coursework at the collegiate level, let alone the high school level, rarely suffices. No engineer’s English and writing experience should end at the age of 16—or even 20 for that matter. That is how you produce poor engineers whose work is hard to understand. (Or, consider any poorly written instructions you have ever read; had the writer had a more thorough education in English, the instructions would have likely been far easier to understand and follow.)

This principle applies to doctors as well. As any online review of a doctor would indicate, empathy is incredibly important for practicing physicians. A good doctor isn’t just made through high scores in chemistry and biology; they must also know how to relate to their patients. For many, this empathy is best learned through art, literature and history—not in a hospital where you are often taught to suppress and ignore your feelings.

In fact, this principle applies to all STEM careers. Given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of many fields, a holistic understanding of all major academic disciplines will become ever more crucial.

And the same is true for politicians, lawyers, historians or anyone else working in non-STEM fields. They too should be educated in coursework outside of their chosen professions. A strong basis in mathematics and the natural sciences—and a basis that goes beyond the high school level—provides students with invaluable problem-solving skills that, if not relevant in their field of work, are relevant in day-to-day life.

Additionally, the flexibility provided by a holistic education will prove more and more useful in the future. A survey from the Pew Research Center found that of those who quit their job in 2021, 53% changed their occupation or field of work. And the number of those who switch careers, often in fields that are in no way related, is only expected to increase.

The skills learned from a holistic liberal arts education better serve those who change career paths. Specializing in only one or two hyper-specific academic disciplines from such a young age is inevitably bound to end in tragedy for those who, upon being hired in their chosen field, find that it is not for them.

Yet, career is not the only reason education should be holistic. A truly meaningful and well-designed curriculum can—and often does—enrich one’s soul. By learning about biology and physics, you come to better appreciate the world around you; by learning about history, you are given context to your existence; and by learning about and creating art, you experience becoming. This is what Humboldt meant by “cultivation of the mind.”

Post-secondary education in the US is expensive. Too expensive. And an often cited means of lowering these costs is to scale back or completely eliminate university general education requirements. That way, students would only have to pay for the courses relevant to their field of study, thereby reducing the financial burden of attending college.

It is true that for many, general education requirements are economically burdensome. At many colleges and universities across the country, enrollment in general education courses costs thousands, or even tens of thousands of dollars. But the solution to these rising costs is not to remove all non-major requirements. Post-secondary education costs must be eliminated through other means, not by excising what little is left of holistic education.

And that is true of all barriers to entering college, financial or not. A holistic education is not one meant to be exclusively earned by the 1%. Only by removing all barriers to education can the benefits of a holistic education truly shine.

The careerist and STEM focus in education is an entirely new phenomenon. While it certainly has provided myriad benefits to society—advances in medicine and flight come first to mind—it has also undoubtedly deprived many of us from what makes us human: things like art, music and history. Life is far too short to pursue only that which provides a wage. Without the things a holistic education provides, life loses its purpose—its soul.

Today’s educational model is still in its infancy; the trivium-quadrivium model existed far longer than the careerist model gaining prominence today. The long term effects of this new model have yet to be seen, and it is unclear whether it will stand the test of time.