The first major literary work I read for an FHS class was Homer’s “The Odyssey.” Though I appreciated the poem’s cultural and literary significance, I ultimately shared the opinion of many of my classmates regarding the work: Homer’s writing is convoluted, dry and just generally uninteresting.

So it came as a complete surprise when, the following summer, I received my own copy of “The Odyssey” as a gift. While hesitant, I gave it a second read.

I am so happy I did.

Somehow, this time, I couldn’t put the poem down.

What changed since my initial reading nearly a year prior? Was it a deep literary maturity I had unknowingly developed? Some newfound scholarly intellect I acquired as a now-rising sophomore? Was it Athena’s magic?

No. It was none of these things. The story had not changed, but the way in which it was communicated to me had—I read a different translation!

I now understand that my initial dislike of “The Odyssey” stemmed not from “Homer’s writing” (I cannot read Ancient Greek, after all), but rather from how the translator rendered the text—the choices they made in tone, structure, and phrasing.

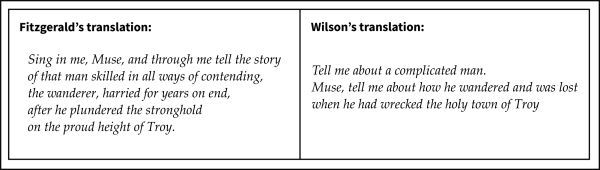

To demonstrate this point, consider two translations of the opening lines of “The Odyssey”: Robert Fitzgerald’s, published in 1961, and Emily Wilson’s, published in 2018.

One need not be a literary scholar to see a clear difference between the two translations. Fitzgerald’s version is grand, full of elevated language; Wilson’s, on the other hand, is direct and contemporary.

Even seemingly small choices alter the tone significantly. Fitzgerald describes Odysseus—the “Man” being referred to in both passages—as “skilled in the ways of contending,” emphasizing his strength and valor. Wilson, however, states only that Odysseus is a “complicated man,” providing his character nuance, rather than grandeur.

A similar tone-altering discrepancy can be seen in the two descriptions of Troy: Fitzgerald’s “proud height of Troy” implies a noble, yet imposing city, whereas Wilson’s “holy town of Troy” suggests a small and sacred community. These differences shape how readers perceive Odysseus and his environment from the very first line.

While these differences might seem rather trivial, they can often shape readers’ interpretations of entire countries and cultures. Take, for example, Fitzgerald’s (and others’) use of “savage” to describe Polyphemus—a cyclops Odysseus encounters during “The Odyssey.” As Wilson notes in the forward to her translation of the poem, words such as these carry specific cultural and historical connotations to contemporary readers—connotations that did not exist in 700 BCE, but which can significantly alter how readers perceive characters and their societies today.

I write this not to bash certain translations or their translators—Fitzgerald’s translation is arguably more poetic, and many happily come to its defense. Rather, I say this to encourage that translations be considered more thoughtfully than they currently are.

As readers, we should be mindful of not just the works we consume, but also the lens through which we are introduced to them. We must recognize that translation always involves interpretation, and this interpretation ought to be considered in appreciating, analyzing or teaching any work—especially those written in a different time and culture.

Perhaps, like me, you have dismissed a foreign work as uninteresting or inaccessible. Or maybe you are considering reading a foreign work for the first time. Either way, I encourage you to explore the translations available to you. The way a story is told matters just as much as the story itself.

Tara • Feb 27, 2025 at 4:01 pm

Excellent piece! This makes me really want to dive into Wilson’s translation. I particularly appreciate the reminder that any translation is interpretation. What could this mean for a society that is founded heavily upon a specific ancient text translated by men? 😉 Food for thought. Thanks!